About a year ago, my taichi teacher held up a sheet of paper with 4 characters on it and pronounced the words in the title of this post.

She has not revisited the page again but the first word “Song” (or “Sung”) is at the core of every class. There is enough in this one concept to keep beginners (who are interested enough) to explore, play, work with. There is always more Sung just a moment away.

This is my current understanding – jotting it down, so I can cycle back to them over time. Also to discuss with my teacher and other friends to refine my understanding.

(When I say understanding, I don’t mean just abstract intellectual, but more embodied and felt but also with an accompanying worded clarity).

I’ve read a few of the taichi classics and these four words (as a group) don’t come up, but the meanings resonate to this student anyway.

“Sōng, Sǎn, Tōng, Kòng” represents four key principles in Tai Chi practice:

1. Sōng (鬆): Also spelled “Sung”, refers to the concept of relaxation or more exactly – loosening. In Tai Chi, Sung is the practice of releasing unnecessary tension – initially this might be your body and muscles but during the process there is a loosening from the day’s tensions – so a loosening of the mind takes place.

Discovering Sung starts by feeling areas of increased tension in ones body:

- hitching up your shoulders

- forgetting to breath

- tightening in slow movements as some “performance” antics

- imbalances from not having alignment

- discovering you are too fast or too slow, or just plain wrong in your movement

By non-judgementally sensing the tightening gives the opportunity to feel the relaxation and just how good that feels.

Sung is not floppy – this is not some extreme “melt on the floor into a pool of jelly” thing, the Taichi student still holds their form and follows the sequence – with each moment the changes in weight means there is enough muscle action happening.

Bio-mechanically a loosening is happening at the joints and muscles hanging off the bones rather than binding to them – more energy is available to your body to maintain its core processes and help with wellness.

More esoterically, the wasteful energy being dropped us united to complete the movement – this is where I suspect the 3rd of the 3 treasures (Shen) is generated. Where attention and practice is not scattered.

I’d suggest that movement can and should come from the loosening. That is counterintuitive but possibly a hint as to what “Qi” might be. When you loosen there is a strength that emerges from the space created when tension is dropped.

By cultivating Sung, the Taichi student can improve their balance, sensitivity, and experience a complete difference to the rest of their day.

I’ve written about Sung before here and here.

There is also a clue to loosening emotions and judgement as well. That’s another blog post!

I have less to say about San, Tong, Kong. I am a beginner and only getting early understanding.

2. Sǎn (散): San is to “spread”. The tightness that Sung remedies is muscular energy locked up in a concentration of location. Sung starts the process of unlocking. So I feel that San is allowing that loosening to dissipate even further.

A very simple experience is Taichi’s preparation position: where the feet standing together simply has the left foot step out to shoulder width. As my right foot takes weight the left foot lifts and any dissipates any energy holding its shape. It’s an instant lesson to discover your foot is arched up, it should be dripping off your leg until the moment when the toes touch at the end of the movement.

Of course you can experience this in all movements and reminds me a the rich experiences of walking meditation in the Mahasi Vipassana tradition.

Beginner students also experience Sǎn in the Yin phase of any movement – the “loosening off” (or yielding) before moving into the next posture. Once you’ve circled into the final phase of a posture you are already circling out with a Yin or yielding way (or at least that is my experience to-date).

Another beginner experience that hints at the martial art practices is the “Lu” or “Liu” in Peng, Lu, Ji, An (Grasping the bird’s tail). Liu has its origins in the martial aspect.

Liu is where you are taking the energy of an opponent and guiding it into a void – the practitioner feels “empty enough” (see Kong) to not meet an opponent’s force head-on but spreading or dissipating their own energy to neutralize or redirect the “attack”. This is why old Taichi guys can beat younger, more energetic opponents – when you are using “Li” (muscular based force, there will always be someone who can overcome you).

I saw this a few weeks ago in a competition where competitor A was easily over 180kg, his opponent B, still solid at 90kg standing at shoulder height of A.

“A” had easily bullied other competitors out of the ring, not expending much energy. When “A” met “B” – it was an ugly bout but I noticed that “B” was rotating around to stay inside the circle and pulsing at “A” – he was oscillating “Liu” and Ji/An very effectively.

“A” was so unfit that he was exhausted and eventually conceded defeat before very nearly needing medical attention. “B” provided a very impressive performance of yielding and Sǎn is at the core.

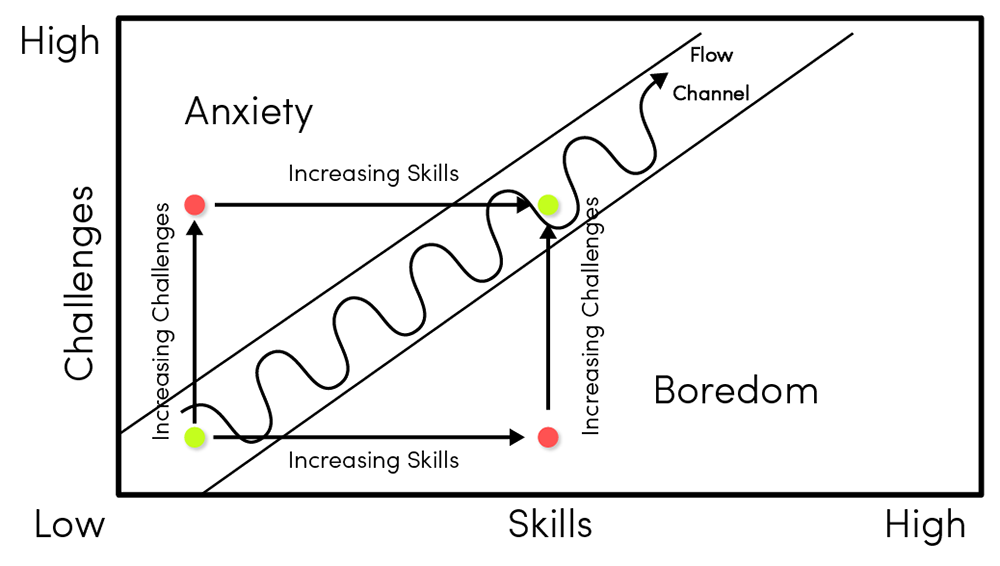

3. Tōng (通): Tōng is experienced as “connection” or “flow.” My teacher encourages us to experience the “energy waves” the sequences are following the natural currents in the body. With enough Song, San you get moments of feeling less like you are doing the “robot dance” and more the continuity and connectedness of the movement.

For me, “Cloud Hands” was my first game-changing experience of Tong – everything happening at once with epic spaciousness was real connection.

Its easy to get very woo and mystical about “Qi” – here we can practically experience the energy each movement takes throughout the body. Initially gross (course) sensations you are starting to pick up on subtleties.

Another type of connection is continuity: The saying “Qi follows “Yi” has been mentioned in other posts. The Taichi student is not “zoning out”, not being intellectually lazy and copying by rote the teacher or other students. The “Yi” (intention) is actively present and knowing what the next phases of the sequence are. I don’t now if this is part of Tong, but its essential for “flow” in the sequence.

Another saying from the Tai Chi classics points to Tong.

“connected like a string of pearls”

Getting more Tong takes time – a natural cultivation where smoothness is not a “fake it until you make it” performance but snippets will come in time, “Yi” and practice.

4. Kòng (空): Kòng means “empty” or “void.” This reminds me a lot of Buddhist emptiness – where something happening is a creation (or fabrication) of the mind on top of sense perception. Victor Frankel said:

“Between stimulus and response there is a space. In that space is our power to choose our response. In our response lies our growth and our freedom.”

Note also that emptiness is required in the purest martial aspect, see the discussion of Liu above in the San section. A great example is the popular novel Musashi by “Eiji Yoshikawa”, readers would remember he was “empty” of all expectations of his opponent and was able to respond with a very pure precision. (Many Asian Kung Fu movies copy this spontaneous spirit).

In Tai Chi, in my limited experience is allowing the other 3 elements of Song, San, Tong to prepare me for openness in the body and mind. By remaining open and receptive, I can allow the distractions of the mind to take a rest.

I know the meaning and experience of Kong is a lot deeper, I’ll give it some time.